By Mike Fall, from his unpublished autobiography ‘Lifecycles’

As I got older, my legs became stronger and so I could cycle further. The summer holidays had begun, so I rode off with my friends to explore the urban wilderness of Woodhouse Moor.

We intrepid explorers could live off the land there – by pinching stuff from the allotments. Then, when we ventured still further, to Beckett Park, we starved, because there were no allotments – or so we thought – and it was to be over 60 years before Ron Davies, a major contributor to The Leodis Archive, put me wise. There were some. Ron knew because he lived on Beckett Park. If we had found them though, we may have become fat kids too.

Having arrived at the Beckett Park bus terminus, we pinched used tickets from boxes at the backs of the buses. The drivers and conductors rarely paid much attention to us as we sneaked on to the rear platform. They always stood in front of the bus whilst they smoked and chatted, before setting off again. We collected the used tickets in the way that boys have always collected things.

Though it is no longer regarded as a traitorous act to buy anything Japanese, and the fad for collecting Pokemon cards came and went without a ripple, we wouldn’t have bought anything from them – even if we had had any money. But we kids were all a little short on details. I thought that I had discovered the details when I saw ‘Bridge on the River Kwai’ many years later.

However, I was wrong. My wife’s father thought the film was a comedy. He had been a prisoner of war, like my own dad. However, unlike my dad, he suffered nightmares about his ‘Japanese’ captors for the rest of his life – the word Japanese is parenthesised because their Korean underlings were, according to my father-in-law, even more cruel than their masters.

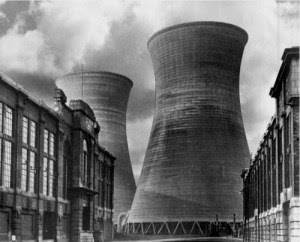

Gott’s Park was the next adventure playground. Once having cycled there, we were free to risk drowning ourselves whilst playing on the banks of the canal. In order to reach Gott’s Park from where we lived though, we had to pass right through the middle of the Kirkstall power station site – and this provided attractions of its own.

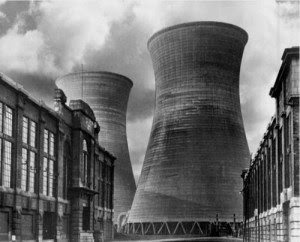

The road through the site passed within touching distance of the giant concrete egg cups which always seem to have pride of place on those pseudo-scientific TV programs about atmospheric pollution and global warming, even though the only thing which comes out of them is water vapour – strictly speaking hot air comes out too, but not as much as comes out of our politicians (allegedly).

As the bases of these cooling towers were completely open, whilst the generator cooling water cascaded down their insides like monsoon rains, it was impossible for us to pass by their open bases without getting soaked when it was windy. We didn’t know that it wasn’t Disneyland, or even an Alton Towers log-flume, but for young lads the world over, wet is wet. In those days there were no queues for the flume, Disney didn’t have a country named after him, and the would-be developers of Alton Towers were still waiting for the M1 to be built.

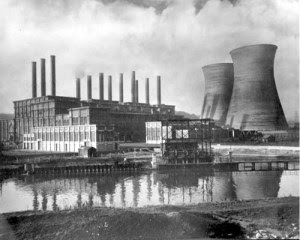

Of course, there was more to a 1950’s coal-fired power station than big egg cups and a soaking… and power wasn’t the only thing that this one generated. The station could just as accurately have been called an industrial volcano, and a huge area adjacent to the plant was given over the disposal of its ash. This area was called Kirkstall. The captive portion of the ash from the furnaces was mixed with water until it looked like thick, grey cocoa. It was then pumped into barren paddy fields to settle, before being carted off. Although filthy, these sludge dumps were one of the more benign products of power generation (even though we boys didn’t help much by lobbing stones into them).

In the station’s earlier days, a dozen stubby steel chimneys pretended to dispose of the smoke. They were no doubt effective enough to drag air through the furnaces, but they were short enough to spew their toxic fumes straight into your face. In addition to their sulphurous fumes, they also dispersed those thousands of tons of airborne ash which didn’t make it into the ash lagoons (as the sludge dumps were euphemistically called). The stuff fell day and night, like a drizzle of fine grit all over the surrounding area.

But at least the Norwegians were happy in those days. Then progress took its toll. The stubble of steel flues was replaced by a huge concrete spire. The new chimney was regarded by the people of Kirkstall as a miracle of civil engineering. However, the people of Burley, where I lived, were not quite so impressed, as the higher chimney distributed its fly-ash much more widely. The Norwegians weren’t all that pleased either – as they woke up to find our new system poisoning their lakes and forests.

My mam wasn’t too bothered about lakes and trees, except on Sundays, when we sometimes went out. But she complained bitterly for the rest of the week, particularly on Mondays: Monday was her wash-day, which she spent up to her armpits in soapsuds. When her clean washing was hung in the yard to dry, it came back in even dirtier than it was before she washed it, so she wasn’t impressed. She wasn’t impressed, either, by the fact that all our curtains had more grit in them than a Tuareg’s tent flap.

The new chimney brought a whole new meaning to gritting one’s teeth too, but even a cloud of fly ash can have a silver lining. As our family were relatively posh, the landing, on which my narrow bed had been cleverly squeezed, had been laid with a strip of linoleum (hence the ‘posh’) and, as the landing window was usually left open, ‘my’ floor was always nice and crunchy.

Although this gave me the opportunity to practice my sand-dancing I was, to my chagrin, already too late for a career in the music hall, for although the Leeds City Palace of Varieties still survives as one of our last remaining music halls, most of the others had gone. Even though the all-time greats, Wilson and Keppel and Betty, were still performing at that time, their long careers in sand-dancing had taken its toll. It had worn down their legs down to such an extent that their dance had become a mere shuffle – and they would soon have to retire. The photo of our house, which is shown above, has a story of its own, but I didn’t know what that story was when I discovered the photo. It had appeared, without a word of explanation, on the Leodis website. However, all it took was an email to Leodis, and the half century old mystery was solved. Someone had decided to demolish our house – and then changed their mind.

The Hollies Park was even further afield than Gott’s Park, and it seemed to be as unlike Kirkstall as it was possible to be. As it was out of reach of most of the chimney ash, you could breathe through your mouth if you wanted. It was special there – because the ‘parky’ was my uncle, and sometimes he’d let me and my best friend Bert go on the putting green, free – but not ‘for free’ – for that term was to be coined ‘for’ later. There was a stream to dam up, and an urban rain forest of rhododendron bushes in which to hide should my uncle’s peaked cap appear on the horizon.

You had to ride past the Headingley tram shed to get to The Hollies. My dad worked there sometimes, as he was a sign-writer for Leeds Corporation. His job was to paint the adverts on the trams. My favourite was ‘KLG Plugs’ because he had fitted KLG spark plugs in our Austin Seven. He said that they made it go faster. Although our Austin Seven was flat out at fifty miles per hour (even with its KLG plugs), travelling at anything like that speed made it difficult to focus your eyes.

Finally, we cycled all the way to Paul’s pond to go stickleback hunting. The pond was right out of the city, deep in the jungle, down a farm track, just over the road from Golden Acre park. On our way there we had to pass the tram terminus at Lawnswood cemetery. In summer, there was always a man at the end of the tram track who sold bright red drinks from enormous glass jars. The jars had real fruit floating inside them and were topped with lids so big that they looked like transparent church bells. The jars gave off an aroma of strawberry heaven which lives on in my mind to this day.

It was uphill from our house to Lawnswood, and so we were always parched by the time we had slogged it up to the end of the tram track. We were never able to enter strawberry heaven ourselves though, we just stood by and watched the rich people drink instead. I believed in the supernatural at that time, Captain Marvel and Superman being high on my list, but I was beginning to harbour doubts about Jesus and his camel story, even then. Today the trams are just a memory, the strawberry man has gone the way of all strawberry men, and both Mam and Dad rest just across the road in Lawnswood cemetery.

I served my time at Queen’s Road Junior School until I was eleven, and one of the two most enduring memories of my incarceration there was the burning pain from Pa Long’s cane. Pa Long knew his trade; no ordinary piece of chair dowelling for him. He, like Charles Ritz, the champion fly-fisherman (& hotel owner), had realised the benefits of flexibility: He cast his piece of whippy split-cane fishing rod across the insides of our tender knuckles as skilfully and lovingly as Mr Ritz himself. Who knows, Pa’s piece of split cane might once have belonged to the man himself.

Corporal punishment wasn’t just tolerated in the kid-scape of our pre-Amnesty International era. It was mandatory. All but the tenderest of people subscribed to the biblical ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’ school of child rearing. So that was that. It was better for our mams though, as they didn’t need to plead with their children at every juncture of the modern ‘taking them to school’ ritual. There were no 4×4 baby buggies in the 1940s, apart from the occasional Willys Jeep, of course, & our mams could barely afford shoes, never mind afford their own transport.

What they could do though, was start their day early, and get on with sandblasting their washing with clear consciences. They enjoyed this freedom, which would be unimaginable today, because they could relax in the knowledge that Pa Long would be only too happy to ‘encourage’ their children to get to school on time… and then to tend them lovingly whilst they were in his care. Not surprisingly, there weren’t many of us who were silly enough to be late, particularly on Pa Long’s mornings for yard duty. The penalty for such a lapse would have been one on each hand with his sawn-off fly rod, and ‘special interest’ for the rest of that day. But even the knuckle cracking didn’t deter the hard cases. Maybe they didn’t register pain like the rest of us. Who knows what they might have suffered at home though, in order to display such stoicism. I have yet to see a claim for repetitive cane injury, so maybe none of them survived to be litigious.

The other, but happier, memory, was that of the bravery of my friend Ron. He deliberately provoked our class teacher into punishing him. This wasn’t quite as stupid as it might sound – as our class teacher at the time was not the much feared Pa Long, and it certainly wasn’t fishing that interested Ron. Our teacher’s chastisement for naughty boys (it was invariably the boys in those days too) was to put the culprit across her knee, pull up one leg of his short trousers, and slap the back of his leg.

Ron wasn’t a masochist, so he didn’t think much to the leg slapping, but he loved the feeling of being sandwiched between a pair of warm female thighs beneath him, and the weight of a pair of ample bosoms resting on his back. So, although my school lacked many of the facilities of our more prestigious public schools, it could still provide comfort for those who needed it most.

I was nearly twelve when I was assigned to my secondary school. The Education Authority asked which school I would prefer. I thought that it was nice of them to ask, and chose to go to Leeds Modern School at Lawnswood. So they sent me to West Leeds High School. And what a strange place it proved to be. The teachers wore black, flowing gowns, we boys were taught Latin and, more importantly, we were segregated from the girls. There were no female teachers in the boy’s half of the school, so I guessed that that was to be the end of bosoms and thighs for a while. The school also boasted a house system, a uniform – with a badge – and a Latin motto: Non Sibi Sed Ludo: Not for one’s self, but for one’s school. I suppose its post-Thatcher counterpart would be Sibi Sibi Sibi – and one doesn’t need to be a classics scholar to work that one out. You didn’t have to wear the school blazer, but if you were foolish enough to be caught outside school without the regulation tie and cap, the prefects had the authority to castrate you – with a wooden ruler.

My new school’s pretensions to the public school ethic provided a stark contrast for a lad from a home where the toilet seat was usually warmed by previous sitters (sic). However, you were allowed to go to school on your bike. They even provided covered cycle racks… so it wasn’t all bad. Had I been granted my choice of Leeds Modern though, I would have started my secondary education there whilst a boy called Alan Bennett was in the sixth form. In that same year, Alan was living over his dad’s butcher’s shop which was next to the Headingley Tram Sheds, where my dad painted his KLG plug adverts. If Alan’s family had not moved to Headingley from Halliday Place in Armley a few years earlier he, too, might have been sent to West Leeds. So I just missed being able to boast that I had gone to school with someone who became famous. I might even have enjoyed the wooden ruler treatment at the hands of a prefect who would one day write ‘The History Boys’.

My new school was at Whingate Junction, just a few miles from where I lived. After a short downhill ride on my bike from my home to Kirkstall Road, the rest was uphill. My journey, though, was punctuated by several potential World Heritage sites – but which never quite made it: the Kirkstall gas holders, Kirkstall swimming bath and wash house, the river Aire, the Leeds and Liverpool canal, Canal Road Armley, Sammy Ledgard’s bus depot, Armley swimming baths and ballroom (the swimming bath became a ‘ballroom’ on Saturday nights when they covered the pool over with boards) and, finally, Charley Cake Park.

The Kirkstall wash house was frequented by a procession of women who all pushed prams – though there wasn’t a baby to be seen. Wartime films were still fresh in our minds in 1950, and the sight of these stoical ladies shoving battered prams, piled high with drab grey clothes, reminded me of newsreel refugees. The siren whine of a malevolent Stuka dive-bomber might have completed the picture only a few years earlier almost anywhere in Europe but, as these prams lurched drunkenly on their buckled wheels, they would have made difficult targets. I found it a little disquieting to imagine that these ladies, with their resigned features, might have once been the sort of young girls that were now setting my own pubescent hormones racing. When I thought that I beheld my own future in their faded pinnies, their turbans, their florid faces, and their arms like Sumo wrestlers’ legs, my testosterone dived for cover.

Although the khaki, sluggish flow of the Leeds and Liverpool canal was clearly visible when I crossed the canal bridge on my bike, the river Aire, though only a few yards away, was visible only from the top deck of a bus. When the weather was particularly foul, I sometimes caught the bus to school. If the bus conductor pretended that he didn’t know that I was fare-dodging, by feigning profound interest in some brick wall or other, the unused fare money would buy half of a small loaf from the baker’s just down the road from the school. If, with the price of the first half of a loaf safely tucked in your pocket, the weather had improved by 4pm, and you decided to walk home instead of paying the bus fare, it was then possible to afford both halves. If you had also managed to sell something to a classmate for a couple of extra coppers that day, the lady in the shop would slice your loaf in half, slap a huge gob of synthetic cream into it, top the cream off with a dollop of jam, and send you straight to heaven.

The elderly couple who owned the tuck shop weren’t overly fastidious by today’s standards, and weren’t beyond biologically stamping your passport to heaven by a well-aimed sneeze into it.

As West Leeds High School (Boys) was only a minimum security establishment, we category D prisoners – having been convicted of passing ‘The Scholarship’ & hence having been sent down for a mere 4 to 8 stretch – were ‘let out’ at 4pm… but not at lunch times. To be let out before 4pm required a written pass from The Governor, without which lunch-time bread was also forbidden. Our post-war school dinners were appalling, so those of us who had acquired a few pence (i.e. riches beyond the dreams of anarchists) had to break out. With the ever-vigilant guards (the prefects) on patrol, climbing the main gate was out of the question. So it was through a hole in the privet hedge, onto the rail embankment, up & over the bridge parapet, cross the road & run the gauntlet of prefects to the shop… as can be made out (just) here.

Of course, we weren’t safe even when we had reached the sanctuary of the shop. In the spirit of ‘do as I say, not as I do’, many of the prefects were clandestine half-loafers too, so we had to sneak a glance into the shop, even before entering. Obviously we weren’t safe once inside either. So we had to post a prefect-spotter on the door, and more than once we plebs were hidden ‘in the back’ by the kindly lady, whilst the prefect errant was being served and dispatched.

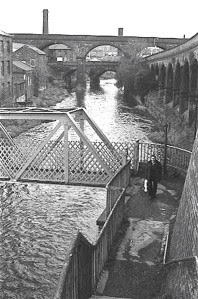

The bus to school crossed The Aire on the road bridge, and this bridge, in its turn, was vaulted over by the huge arches of the railway viaduct.

However, there was a shortcut for those of us who were on foot… and in the know. Canal Road turned sharply through about ninety degrees after crossing the bridge, and then, almost hidden in the inner elbow of this tight corner, there appeared to be what was little more than a hole in the wall. If you dared to pass through this hole, you could steal a view of the river below you… but that was not all. Somehow, a gravity-defying narrow iron staircase had been stuck to the side of the deep brick canyon which constrained the river.

These stairs led down to a rickety footbridge. You didn’t need to be all that brave to walk across it in the warm light of a summer’s afternoon when the river was low and its turgid stream flowed sullenly around all the rubbish which cluttered its bed. I was still only eleven when I was introduced to its rusty iron architecture by an older friend… and enjoyed his moral support as well as the afternoon light when I crossed over it for the first time.

As my first school term started in September, the summer’s warm light very soon gave way to the cool twilight of autumn, and then to the bleak, cold blackness of winter in an industrial city. If you look carefully, the photo shows the remains of a gas-lamp. Although the lamp did actually work in my day, one can imagine the deep unease that a lone boy of twelve might feel on being suspended above the swirling torrent of a winter flood.

This particular boy still suffers nightmares in which the sputtering, pallid light of the gas-lamp serves to highlight, rather than to diminish, the hypnotic attraction of a malevolent, black maelstrom. Of course, there was so much more to life in those days than malevolent maelstroms. Leedsloiners believe that this footbridge is unique and boast, openly, that it is the only place in the world where a sightseer can stand on a bridge, to look under a bridge, to see over a bridge, and see the Town Hall clock. The photo doesn’t allow the viewer to actually see the clock, but it’s well worth making a trip to this special part of Leeds just to see what time it is when you get there.

On reaching the far side of the bridge, a narrow path soon led you beneath the overhang of the fire escape which belonged to Charles Thackray’s factory. I didn’t realise it at the time, but there must still be a fortune awaiting the entrepreneur who mines the river bed just upstream of the footbridge. This gem of industrial archaeology, though not yet shown on any TV documentary, nor even to be included on the Heritage Trail, was to provide sobering examples of man’s inhumanity to both man and moggy. It was also the site of Jackie Bryant’s Revenge…

As The Thackray Museum wasn’t founded until 1997, Charles Thackray trod the Heritage Trail only belatedly, so it was under the auspices of a less renowned Mr Thackray that both the stainless steel deposits, and the treasure trove of pocket artefacts, were laid down on the bed of the river Aire. Although he owned the factory, Mr Thackray would, in all probability, have known nothing of Jackie’s Revenge so, as no formal record has been kept, perhaps I should bear witness. Barely ten years after my leaving West Leeds High School (Boys) 1953, aged fifteen, I was in my third job, and had the good fortune to be working with several young men who had served their apprenticeships at Thackray’s – and it transpired that they had been working at the very factory under whose fire escape I used to pass on my way to, and from, school. Apprenticeships were much more common then, because fewer than 5% of school leavers went to University, and there weren’t enough jobs as hole-diggers, say, to employ the rest of us. These Thackray alumni told me how mistakes were sometimes made in the manufacture of batches of stainless steel surgical instruments and how, if the disposal of the faulty items could be arranged before the foreman found out, no one would be any the wiser.

Apprenticeship proved, arguably, to provide a broader educational experience than the cloistered life of University and, if so, Thackray boys were inducted into ‘real life’ somewhat sooner than their academic counterparts. Coincidentally, there were far fewer fat kids (as we were allowed to call them in those days) so a small part of the Thackray induction was to be dangled over the river by one’s feet. This ritual was performed from the same fire-escape platform under which I passed whilst walking to and from school – and from which the faulty instruments were dumped surreptitiously into the river.

This ‘reverse hanging’, was more benign than ‘the real thing’ which still took place in Armley gaol and so was used as a punishment for only minor misdemeanours – thus alleviating the boredom of the time-served men. Of course, in the interests of health and safety, it was entrusted only to those more senior staff members who boasted a strong grip. However, should the struggling danglee happen to have any loose items in his pockets, as was often the case, they would be surrendered to the river and so it was this practice which accounted for the build-up of pocket artefacts on the river-bed.

The nearby asbestos factory was less fun altogether. Although none of us knew it at the time, the last will and testament of J. W. Roberts and Co. had already been drawn up long before I passed their Canal Road Works on my way to school each day. However, many people would have to wait patiently for their dark inheritance. A certain Mr. Justice Holland would rule, many years later, that the dangers of breathing asbestos fibres were well known in the trade as early as 1933. Strangely though, that information was not passed down to the workers – nor to the people who lived nearby. It certainly wasn’t passed down to me.

By the time I had pedalled up Canal Road into the flurry of deadly fibres from Roberts’, I would be gasping from the effort, so I must have inhaled enough airborne asbestos to stuff a fireproof cushion during my time at West Leeds High School. Epidemiological studies have since concluded that I did the right thing though when I decided to stop smoking (at the age of 11). Asbestos and tobacco smoke have proved to be infinitely more dangerous in combination. Even so, it is said that one single microscopic asbestos fibre lodged in your lung is enough to cause lung cancer. Asbestos-induced mesothelioma can also take over forty years to develop, so I continue to count my blessings.

Our school cycle racks provided a clandestine meeting place. ‘Behind the cycle sheds’ was a cliché, even in the 1950s, so they were frequented by the usual band of smokers and ne’er-do-wells – in addition to ourselves: the cyclists. We would compare our bikes, our stories and our aspirations. We would critically appraise the real bikes which were exclusively owned by the sixth-formers – an occasional one of whom might even deign to speak down to us if he thought that none of his peers was looking.

By the time I was 12, I had extended my cycling exploits to riding an oversize ladies bike with balloon tyres and a back-pedal brake. I had also acquired a rear carrier with a spring clamp, a pump which required no flexible adaptor, and a lock which clamped onto the rear stay. You could not buy any of these items in Britain though: I bought them in Germany.

When my dad finally came home from the war, he explained that he had been imprisoned in a work camp at Lavamund, near to Graz in Austria, where he had been made to help to build a dam for Mr Hitler. Although he never met ‘Der Fuhrer’, he said that most of the Germans seemed all right, but that he didn’t like the Australians much. At first I wondered if we might have been at war with the wrong people. Later I realised that, in Graz at least, most of his ‘Germans’ would have been Austrians, and perhaps the Austrians weren’t as bad as Germans. Then I remembered that Hitler was an Austrian, so I had to give in – at least until my School History lessons caught up.

The logic of armed conflict was, however, clarified for me when the brave TV journalists, and their even braver camera-men, provided an armchair view of the carnage in ‘the former Yugoslavia’. I guess that camera men have to be braver than journalists because it is easier to run away from danger if you are only wearing an earnest expression… The weight of a camera and a heavy battery belt must be another matter altogether.

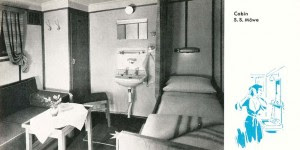

I think that my trip to Germany was my dad’s idea, but both Mam and Dad took me in the car to the Albert Dock in Hull and they put me, alone, onto the ss Möwe: Georg was to collect me off the boat if we made it to Hamburg. It proved to be like a school holiday, but it was much better because there were no masters. The ship’s captain gave me my own cabin with a bunk, a sink and a porthole. The food was marvellous, I was left completely alone, except at mealtimes – and was free to explore the ship. I soon found a door marked ‘BAD’ which, to a lad who was learning French at school, and not German, did not sound too good. But I was a twelve year old boy – so I opened it. When confronted by a very small empty room, I couldn’t imagine what might be bad about it. Wondering, also, why there might be a tap on the wall which was not apparently connected to anything, I turned it on – just to check.

After receiving an impromptu soaking, I rushed back to my cabin, donned my gabardine raincoat and rushed back to turn off the tap. My swift action, I believed, saved the ship from being flooded and sinking. I had turned on the ship’s only shower! As my decisive action had averted a maritime catastrophe, we all reached our destination safely. When we docked, Georg was there to collect me – but Hamburg was a bit of a mess. It still looked like a bombsite, even though the war had been over for more than 5 years. I went home with Georg on the train. He lived with his mother in a village near Oldenburg. She didn’t speak English, except to call me Mickey Mouse, and I didn’t speak German. She was kind to me though & she lent me her bike (the one with the balloon tyres and back-pedal brake) and I liked her.

Georg had been a prisoner of war at a camp on Butcher Hill in Leeds. My dad invited him to our house for Christmas after seeing an appeal in the Yorkshire Evening Post. They became good friends and Georg often visited us. He was allowed out of the camp, but he wasn’t allowed to go back to Germany – even though the war was over. My dad said it was because he had been in the S.S. Parents were much more trusting in those days, or at least mine were. Can you imagine any self-respecting mummy letting her child out of her sight today before he/she/they escape/s to university?

Perhaps my parents thought that S.S. was short for Sunday School.

The school where Georg was a teacher was just over the road from his house, and I quickly became quite a celebrity with the children there. I learned more German in my four weeks in Germany than I learned French in four years at school – which I later proved by failing my French ‘O’ level.

The German children seemed very interested in the games we played in England, particularly a game we called ‘hot rice’ which was new to them – but they were fascinated by Winston Churchill. They had been told that he ate live babies and nothing I said would change their minds. Of course I wasn’t absolutely sure about his wartime diet myself… After all, it wasn’t only Adolf that had a bit of a strange look about him, was it? My borrowed ladies’ bike was too big for me, but I was soon off for rides around the village when the children were in school. My favourite place of all was the blacksmith’s forge. After having my face fried by its searing heat, I have been in love with hot metal, hammers and the clanging of anvils ever since.

When the children were not in school I was never short of a companion. Most of them seemed to be quite poor and one of the poorest, Karlheinz, became a particular friend. He, like several others, came to school barefoot, and when I went home with him we drank hot water with milk in it because his mum couldn’t afford to buy tea. She was very friendly and we all sat on the sofa looking at their photograph album. Karlheinz was very proud of the photographs of his dad. It disturbed me that his dad was dressed in an ‘enemy’ military uniform like the ones I had seen at the cinema. The uniform didn’t matter though – because Karlheinz’s dad was dead. He had been killed at Stalingrad. I couldn’t remember having heard the name Stalingrad before that, but I can remember thinking it sounded bad – like the word Golgotha, which I had heard at church. I suppose though, that names like Peebles and Chipping Campden might sound a bit odd to a Cossack.

On each side of the road there was a flat, dusty cycle track, and I was surprised to find that it went all the way to Oldenburg. I cycled there a few times to visit the swimming baths with my new friends. They even had cycle tracks in the town centre. The Germans used bikes much more than we did in England, and I found it puzzling that so many of them had huge logs clamped under the spring clamps of their rear carriers. These ‘logs’ turned out to be loaves of bread. They just looked like logs of wood. However, as I discovered later, they also tasted like wood. When my dad came home, he had told me about German ‘black’ bread. Rye-bread had been given to him by the Weight-Watchers in the Third Reich as part of a calorie-controlled diet. When I visited Germany, myself, everyone ate the stuff… and I had thought that my dad had been made to eat it as a punishment for being English.

My holiday, which seemed as though it would last for ever, suddenly began to race by and, before I knew it, I was heading back to Hamburg for my return on the ss Möwe. Although I felt sad that my holiday was almost over, I looked forward to the promise of adventure and further exploration of the ship on my return voyage. My mouth watered at the thought of the food too but, sadly, it was not to be realised. The return crossing was so stormy that I wasn’t even able to stand up. That didn’t matter though, because I spent all the time lying in my bunk, feeling seasick. I ate nothing – and I felt as though I had thrown up everything I had ever eaten in my life. I did have one adventure though. It lasted for the five seconds that it took me to stagger across my cabin to look out of the porthole. The spume-flecked waves outside were a terrifying black, and they towered above our rolling ship as high as houses. I was mortified.

When the ss Möwe finally docked at Hull, I descended its rickety gangplank with my battered suitcase and mixed feelings. I was profoundly relieved not to have been lost at sea, but disappointed that the best holiday I had ever experienced was now over. I felt a strange sadness too, in knowing that I would never see the ship again. However, I was in for another surprise, but it took me a while to discover my mistake. Some twenty years later I was sitting in the cinema with my wife watching a film called ‘The Prize’ which starred Paul Newman. About half way through the film, he boarded a ship in Stockholm to rescue a fellow Nobel laureate from a bunch of East German ‘baddies’ (how times, & ‘baddies’, change). The ship in the film was the ss Möwe but time and the elements had taken their toll. She was now a tired and bruised wreck, weeping rust. On seeing my ship in such a sorry state, I almost wept too.

The moment we arrived back home from the docks, I was down in our cellar fitting the new accessories to my bike in readiness for my return to school. The bittersweet emotions of the first day back, with its displays of stiff new clothes, new spots, and new sproutings of body hair, soon settled into the steady grind of another year. The high-point of the return for the cycling fraternity though, was the appearance in the cycle racks of the brand new Armstrong Moth racing bike. Its new paint glistened in the slanting autumn sunlight: It had a five-speed derailleur gear and it was owned by a fifth-former! Was this a sign of things to come? Might we of the second year have only another three years to wait for ours? In the meantime, I was flattered by the interest shown by my friends in my recent adventures, and now, as a second-year myself, I was no longer a ‘sprog’. Life seemed rosier. In my boyish naiveté I couldn’t begin to imagine that my days of cycling to school were numbered, and that soon my shiny new German carrier would, like the ss Möwe, rust and sag under the strain of heavy-duty service. Fate had already decreed that I was to become Ilkley’s ‘over-river laddie’.

Photos by kind permission of Leeds Library and Information Services, www.leodis.net.

Ripping read! Well done ! Memories never leave us, do they! They say everyone had a book in them, Social history is often lost because people don’t record their memories. Look forward to its publication

Thoroughly enjoyed this ! I think I must be about the same age as the writer because so many things tallied with what I remember too even though I lived in North West Leeds. Incidentally, I attended Lawnswood High School for girls………we never ever fraternised with The Modern School even though it was a few yards away!We were not allowed to even go as far as the third window on the field side of the Swimming Baths, which separated the two schools. However, as we got older and were allowed to go ‘down the field’ in the Summer at Dinner times, We discoverd the shared ‘Jumping Pit’!!!

No one to stop the fraternising there if you were cautious!!!